The C++ programming Language

by Tyler Swann

This book assumes you are using a C++17 compliant compiler but concepts and topics from later standards are also covered, notably C++20. See the “Installation” page of the “Getting Started” Chapter for more details.

This book is under active development. Much of the material is absent, incomplete or subject to change. If you have suggestions create a discussion or issue on GitHub.

Introduction

Welcome to The C++ Programming Language, an introductory book aimed at teaching C++. C++ is a high-level, general purpose, multi-paradigm programming language aimed at giving developers precise control over their programs while also being able express many kinds of abstractions, making the C++ a very powerful language.

Who/What is C++ for?

C++ was designed for building systems and embedded software in resources constrained contexts. These are systems that prioritize performance, efficiency and flexibility of use. C++ allows developers to write fast code that can run or make any kind of system. If you want the ability to build helpful abstractions but needs to run in a constrained environment and use resource as effectively as possible C++ will get you there.

Who is this book for?

This book is generally aimed at people who have programmed before but can be read by those still early in their learning journey. This is to say you should have an idea about what a program is and understand common programming concepts. The aim is to make this book as approachable to as many people as possible. It is possible to read this book without any prior experience to programming but some concepts may not click as quickly if you have never programmed before. The purpose of this book is to showcase how to program using C++ and explore the capabilities the language possesses.

Note

Not every topic or capability of C++ will be explored in this book. For a comprehensive reference on the language explore cppreference.com.

Important

Author’s note on C++ Standard Used in this Book

Currently this book only covers up to the C++17 Standard, even though C++20 (2020) and C++23 (2023) have been released since and C++26 (2026) is actively being written, C++17 is the most supported version by compilers across all new changes. C++20 is nearly there with Modules being the main thing that remains to be implemented however, there is not much that was introduced C++20 that I plan to cover in the immediate draft and thus setting the baseline at C++17 narrows my focus to ensure the foundation is solid. Future versions of the book that introduce features from later standards will likely result in the suggested baseline being increased to C++20.

How to Use This Book

In general, this book assumes that you’re reading it in sequence from front to back. Later chapters build on concepts in earlier chapters. Some chapters will explore creating mini projects that combine concepts from recent chapters to allow you to get some experience writing complete C++ programs.

Tip

You can also search for specific content using the search button in the top left or by pressing the S key.

Synopsis

- Getting Started, explains how install the necessary tools for compiling C++ programs

on various platforms like Windows, macOS and Linux. It also goes through writing a

classical

"Hello, world!"program and will discuss the anatomy of a basic C++ program and using the CMake build system. - Project: Guessing Game, is the first project chapter where you will build a simple ‘number guessing game’. This will introduce you to compiling and building a C++ program and utilising various pieces from C++ at a high level, with later chapters offering more details.

- Common Programming Concepts, will cover the basics of the C++ language from variables and data types to creating functions and controlling the execution flow of a program.

- Ownership, will cover C++’s ownership model and how you are able share data or even transfer data ownership.

- Structured Data will look at how to create custom types using structures and classes.

Planned

- In Managing Projects we’ll use CMake to compile multiple files, manage dependencies and create libraries.

- Error Handling will look at the various ways to verify the correctness of your programs at compile time. We will also look at recovering from errors to prevent crashes.

- Containers explores the most commonly used container types available in the standard library.

- Templates covers C++’s meta-programming capabilities that allow you to write code once and have the compiler generate the implementation for you.

- In Algorithms we’ll explore the plethora of standardised algorithms available in the standard library and how they interact with containers.

- The IO chapter will look deeper at C++ IO capabilities using streams and explore the filesystem library.

- In the Memory chapter we will explore how to safely (and unsafely … for science) control memory.

- In Concurrency we will look at how to make our programs run in parallel using a myriad of concurrency concepts while ensure safe access and manipulation of shared data.

- The appendices hold extra information may be of use to the reader but do not fit in

elsewhere in the book.

- A - Operators

- B - Value Categories

- C - Standard Versions

- D - Recommended Compiler Flags

A - KeywordsD - Compilation PipelineF - Compiler Vendors

Possible Future Chapters

- IO Project, will look at utilising ideas from previous chapters in order to build a

tool that replicates a subset of the functionality of the command line tool

grep. - Algorithms, will showcase a few of the common algorithms available in the C++ standard library and they can be used to manipulate any of the standard containers in an expressive and generic manner. We will also cover the concept of a range and a view and how they allow use to write composable algorithms.

- Improved IO Project, will look at improving our IO project from Chapter 11 by utilising the standard algorithms.

- Object Orientated Programming In C++, covers C++ support for write object orientated code and how it contrasts to the rest of the languages features and object oriented principles you may be familiar with from other languages.

- Date, Time and Localization, introduces C++ support for working with time and dates how to change the locale currently being used to express said times and dates.

There is no wrong way to read this book; if you want to skip ahead, go for it! You might have to jump back to earlier chapters if you experience any confusion. But do whatever works for you.

An important part of the process of learning any programming language is learning how to read the error messages the compiler displays, which can be challenging for large codebases, especially if they are written in C++ (although this is improving). Error messages no matter the language will offer key insight into where the compilation of a program failed and in the case of C++, why it failed, which will guide you toward working code. As such, I’ll provide many examples that don’t compile along with the error message the compiler will show you in each situation. Know that if you enter and run a random example, it may not compile! Make sure you read the surrounding text to see whether the example you’re trying to run is meant to error.

Note

The error message style and content can be dramatically different given a different compiler, compiler version and standard of C++ being used.

Source Code

The source code from which this book is generated can be found on GitHub. Refer to the supporting docs on the books repo for details on how to contribute changes, fix typos or create new content for this book.

External Resources

Getting Started

Let us begin our journey! In this chapter we will discuss:

- Installing C++ on Linux, macOS and Windows

- Creating a C++ program to print

Hello, world! - Using CMake to create cross-platform builds.

Installation

Each platform or Operating System (OS) has a different set of compiler tools so the following sub-chapters will outline how to get setup on each platform.

Available C++ Compilers

| Compiler | Description | Windows | Linux | MacOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) | A collection of compiler technologies for many different languages including C, C++, Objective-C, Ada, D and Go. Part of the GNU project and the default compiler on Linux. | ✅1 | ✅ | ✅ |

| Clang | A compiler frontend and build runner that is a part of the LLVM Project. Used to compile C, C++ and Objective-C. | ✅2 | ✅ | ✅ |

| Microsoft Visual Compilers (MSVC) | Microsoft’s proprietary compiler toolchain for building C and C++. Usually installed with the Visual Studio IDE. | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

Important

The use of

$or>as the first character on a line in any code block for a shell (commands etc.) is used to indicate the prompt with the command following. This is used to clarify a shell code block that contains commands and the (generally) expected output. You do not need to copy the$or>when running commands.

Linux

Installing GCC and Clang on most Linux systems is relatively trivial. Most of the time it requires just installing the GCC or Clang package and some supporting developer tooling packages. These are often bundled together to make installation as simple as possible.

Installing

Depending on your distribution you will use a different package manager and package upstream repository, therefore some package names might be different than what is listed below. Consult your platforms docs for the most seamless way to install a C++ compiler if the below commands fail.

# Debian, Ubuntu, ElementaryOS, Linux Mint, Pop!_OS (APT)

$ sudo apt install build-essential gdb clang llvm cmake

# RedHat, CentOS, Fedora (DNF)

$ sudo dnf install make automake gcc gcc-c++ kernel-devel gdb clang llvm cmake

# Arch, Manjaro (Pacman)

$ sudo pacman -Sy base-devel gdb clang llvm cmake

# OpenSUSE (Zypper)

$ sudo zypper install -t pattern devel_basis

$ sudo zypper install gdb clang llvm cmake

Verifying Installation

To verify the install worked for either GCC or Clang we can run the compiler programs with the version flag and ensure the install has been successful. You should get something like the following output:

# Verify GCC

$ g++ --version

g++ (Ubuntu 11.4.0-1ubuntu1~22.04) 11.4.0

Copyright (C) 2021 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This is free software; see the source for copying conditions. There is NO

warranty; not even for MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

# Verify Clang

$ clang++ --version

Ubuntu clang version 14.0.0-1ubuntu1.1

Target: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

Thread model: posix

InstalledDir: /usr/bin

Tip

Any details displayed from verifying a given newly installed tool may differ to what is displayed in this book.

Tip

- The name of GNU’s compiler toolchain is ‘GCC’ aka GNU Compiler Collection. This is in contrast to the CLI tool called

gccwhich stands for GNU C Compiler.- The C++ compiler from GCC is called

g++. Make sure to use this command when compiling C++ code.

We will also want a tool to help manage larger projects and allow us to build on different machines from the same source. CMake is one such build tool for C++ projects. You would have already installed CMake when you installed the C++ compilers earlier as we added CMake to the install list. You can verify by running:

$ cmake --version

cmake version 3.25.1

CMake suite maintained and supported by Kitware (kitware.com/cmake).

Windows

Windows has many different compilers at its disposal. Some offer native support to building against the Windows runtime while others will emulate a UNIX (the predecessor to Linux and BSD) environment to aid in porting software built for UNIX-like systems. As the specifics can get confusing, this book will only cover the installation of Window’s native compiler toolchain MSVC.

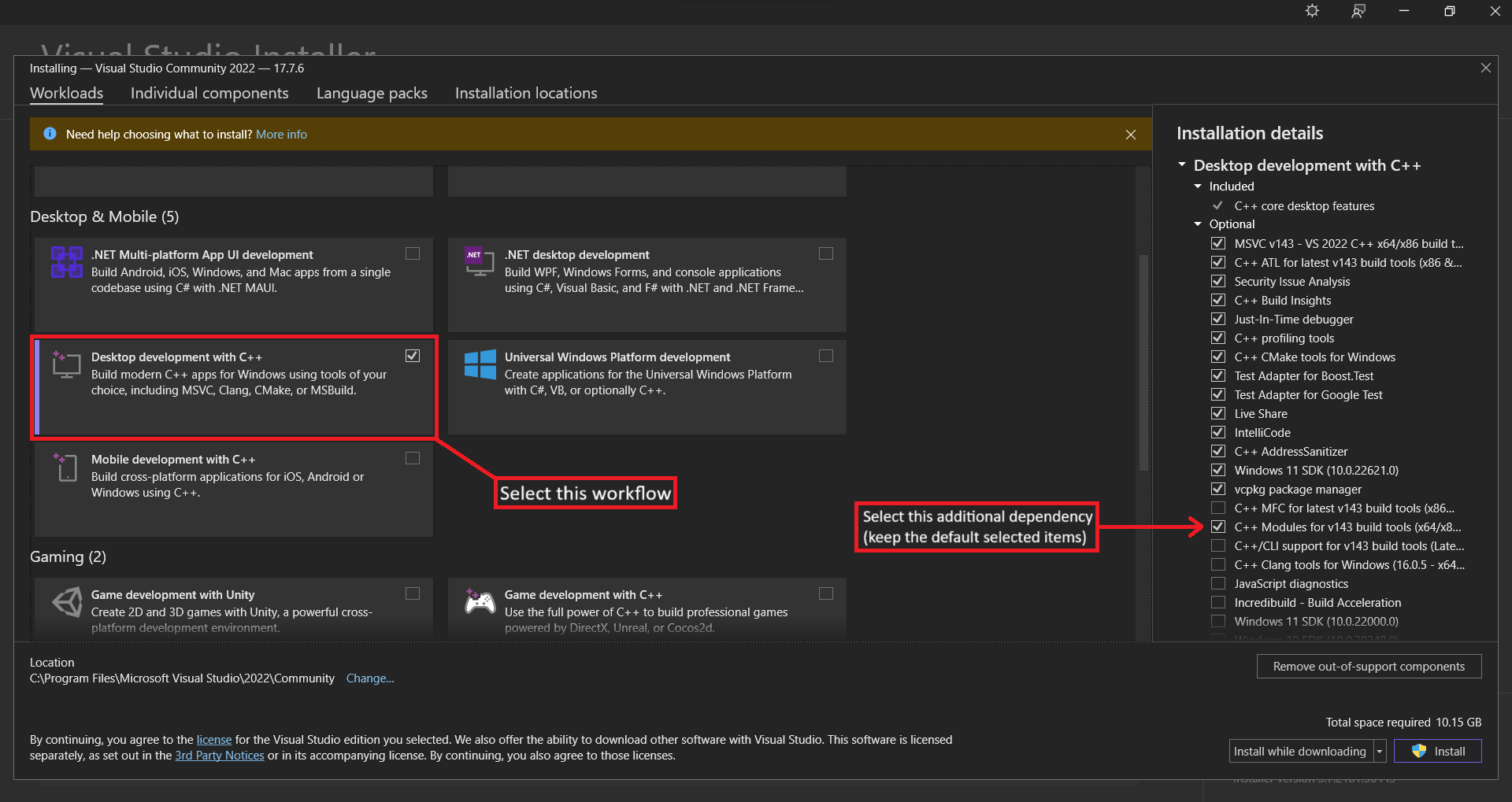

MSVC Installation

The Microsoft Visual C++ (MSVC) compiler is Microsoft’s official toolchain for building

software natively on Windows. It is installed with the Visual Studio Integrated Developer

Environment (IDE). MSVC (and the whole Visual Studio suite) can be obtained from

Microsoft’s official download page. Make sure

to select the correct edition (community being the free version) and click ‘Download’.

This will download the setup program VisualStudioSetup.exe, which is used to install

and configure Visual Studio Installer (VSI). The VSI allows you to select which tools and

technologies from the Visual Studio suite you want to install. Once you have installed

the VSI, start the program and you should be presented with some default tool

configurations (workflows). For developing with C++ you will need to select the ‘Desktop

development with C++’ workflow. You will also want to tick a few optional features as

well (found in the side bar).

Finally, click the ‘Install’ button in the bottom right of the window to start the installation.

Verifying MSVC Installation

To verify you installed Visual Studio correctly you can open the newly installed ‘Developer Command Prompt for VS’. This prompt is needed in order to load the MSVC tooling into the prompt as it is not including by default in CMD or PowerShell. Simply run the following command to verify the install of the compiler.

> cl

Microsoft (R) C/C++ Optimizing Compiler Version 19.37.32822 for x86

Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

usage: cl [ option... ] filename... [ /link linkoption... ]

Note

Any details displayed from verifying a given newly installed tool may differ to what is displayed in this book.

Tip

Alternatively you can follow Microsoft’s tutorial for creating a new C++ VS Project. This will be more convenient than opening a ‘Developer Command Prompt’ every time you want to compile a program and having to run the

clcommand manually but it takes more work setting compiler flags etc. for simple projects.

CMake is a build tool for C++ projects. It is used to manage different configurations for a projects. You can download the latest release from CMake’s Release Page (scroll down to ‘Latest Release’ not ‘Release Candidate’). You can verify it was installed correctly by opening CMD and running.

> cmake --version

cmake version 3.25.1

CMake suite maintained and supported by Kitware (kitware.com/cmake).

Installing Git

We will also need to install Git in order to install a particular package later. Git can

be installed by going to the ‘Git for Windows’ installation

page and selecting the correct version (eg. x64 for 64-bit systems) and following the

installation Wizard. Be sure to select the option for adding Git to the PATH.

MacOS

To install GCC and Clang on MacOS we will need Apple’s developer toolchain called Xcode and a package manager for MacOS called Homebrew.

Installation

To build almost anything on MacOS we need the Xcode developer suite. This is a set of libraries, environment configurations and binaries used at the core of all Apple software products. The full installation can be found on Apple’s developer page (requires a login) but this is an extremely large package requiring ~40Gb of disk space. Luckily there is a much smaller CLI package that just installs the necessary tooling for working with software from the terminal. One of these tools is the Clang compiler. To install GCC you will need the Homebrew, a package manager which will by default install the latest stable version of the GCC formula. If you need a different version you can can check the GCC formula page for available versions. To install these packages, open the ‘Terminal’ app and run:

# Install Xcode CLI tools

$ xcode-select --install

# Install Homebrew

$ /bin/bash -c "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/HEAD/install.sh)"

# Add `brew` command to your PATH

$ (echo; echo 'eval "$(${HOMEBREW_PREFIX}/bin/brew shellenv)"') >> ${shell_profile}

# Install GCC

$ brew install gcc cmake

Verifying Installation

To verify the install worked for either GCC or Clang we can run the compiler programs with the version flag and ensure the install has been successful.

# Verify GCC

$ g++-13 --version

g++-13 (Homebrew GCC 13.2.0) 13.2.0

Copyright (C) 2023 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This is free software; see the source for copying conditions. There is NO

warranty; not even for MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

# Verify Clang

$ clang++ --version

Apple clang version 15.0.0 (clang-1500.0.40.1)

Target: x86_64-apple-darwin22.6.0

Thread model: posix

InstalledDir: /Library/Developer/CommandLineTools/usr/bin

Note

Any details displayed from verifying a given newly installed tool may differ to what is displayed in this book.

Tip

- The name of GNU’s compiler toolchain is ‘GCC’ aka GNU Compiler Collection. This is in contrast to the CLI tool called

gccwhich stands for GNU C Compiler.- The C++ compiler from GCC is called

g++. Make sure to use this command when compiling C++ code.- You must specify the versioned

g++command in order to use the Homebrew version of the command. You can find the default version installed by runningbrew info gcc. We must do this because the regularg++command redirects back to Apple’s Clang implementation.

We will also want a tool to help manage larger projects and allow us to build on different machines from the same source. CMake is one such build tool for C++ projects. It is used to manage different configurations for a projects. You would have already installed CMake when you installed the C++ compilers earlier with Homebrew as we added CMake to the install list. You can verify by running:

$ cmake --version

cmake version 3.25.1

CMake suite maintained and supported by Kitware (kitware.com/cmake).

Hello World

Now that you’ve installed a C++ compiler, its time to write your first C++ program. It is tradition when learning a new programming language to write a program that prints “Hello, world!” to the screen and we’ll be doing the same.

Tip

“Hello, world!” was first introduced as a teaching mechanism for people learning a new programming language in Brian Kernighan’s 1972 “A Tutorial Introduction to the Language B”.

Creating a Project Directory

First, you’ll create a new directory to store you C++ code. It is a good idea to create a ‘projects’ or ‘dev’ directory within your ‘home’ or ‘user’ directory in order to store any project you might develop for this book and beyond. Open a terminal and run the following commands.

Shell Script

mkdir ~/projects

cd ~/projects

mkdir hello_world

cd hello_world

touch main.cxx

PowerShell

New-Item -Path . -Name "projects" -ItemType "Directory"

Set-Location projects

New-Item -Path . -Name "hello_world" -ItemType "Directory"

Set-Location hello_world

New-Item -Path . -Name "main.cxx" -ItemType "File"

Command Prompt

mkdir "%userprofile%\projects"

cd "%userprofile%\projects"

mkdir hello_world

cd hello_world

echo. > main.cxx

Writing and Running a C++ Program

Within this new ‘hello_world’ directory we have created a new file called main.cxx.

This is called a C++ source file. A C++ program is then built from one or more of these

files. We use the file extension *.cxx to denote that this file contains C++ source

code. If a filename contains multiple words the convention is to separate the words with

an underscore eg. hello_world.cxx over helloworld.cxx. Now open the file you have

just created and copy the code from below into the file.

#include <iostream>

auto main() -> int {

std::cout << "Hello, world!\n";

return 0;

}

Tip

C++ source files can have various different extensions such as

*.cpp, or*.c++however, for this book the*.cxxstyle will be used. Is also good practice to use the same extension type across a project so no matter which one you use, just be consistent.

Save the file and return to your terminal open to the ~/projects/hello_world directory and run the following commands….

…. on Linux or macOS ….

$ g++ -std=c++17 -o hello_world main.cxx

$ ./hello_world

Hello, world!

…. on Windows ….

:: Must be done in a 'Developer Command Prompt for VS ...'

> cl /std:c++17 /EHsc /Fe: hello_world.exe main.cxx

> .\hello_world.exe

Hello, world!

If you see “Hello, world!” printed on your terminal, congratulations, you’ve officially written your first C++ program!

Note

- You can swap the

g++command with theclang++command if you want to use the Clang compiler instead of the GCC compiler.- The

-std=c++17(GCC/Clang) and/std:c++17flag options specify the compiler to use the C++17 (2017) version of C++. The-o <name>is used to specify the name and/or directory for the compiled program.

Anatomy of a C++ Program

Let’s go into some more detail on the structure of our “Hello, world!” program. The first component to cover is:

auto main() -> int {

}

This declares a function called main. The main function is known as the program’s

entry point, meaning main is the very first function that runs in every executable C++

program. This declaration of main takes no parameters and returns an integer (int).

If there were parameters they would be declared within the parenthesis (). The body of

the function is wrapped in curly braces {}.

The body of the function contains the following two lines:

std::cout << "Hello, world!\n";

return 0;

The second line returns a status code from main to the (OS) indicating whether the

program run successfully or not. A status code of 0 indicates the program ran was

successfully with any other value indicating the program failed.

The first line is where the action occurs! We start by accessing the symbol cout from

the namespace std “(usually pronounced stood) using the namespace resolution operator

::. cout is a global character output stream that is linked to stdout ie. your

terminal’s output (you’ll learn more about streams and IO in later chapters).

.

We can push characters through the stream using the << operator where the left argument

must be an output stream and the right argument is a series of characters, numbers or a

string. In this case we are pushing the string literal "Hello, world!\n" through the

stream. We use the \n character to specify a newline to be printed after our string

has been written to the terminal.

You’ll notice that we end the line with a semicolon ;. Semicolon’s are used to indicate

the end of an expression.

Note

The operator

<<has been overloaded for use withcout(and other output streams), as such it is only defined to work with C++’s primitive and standard library types. You would need to provide you own definition for custom types.

You’ll also notice at the top of the file the following line:

#include <iostream>

This is a preprocessor instruction, more specifically it is an instruction use to import

the ‘iostream’ library into our program. This is where the symbol for the cout output

stream comes from. We include libraries by utilising the preprocessor directive

#include which basically copies and pastes the contents of the file indicating within

the <> symbols into our program, which in this case is the file ‘iostream’. Assume this

file’s location (and the location of any others used in the same manner) is known to your

compiler unless specified otherwise. Files imported using #include are known as

headers.

Compiler Flags

Compilers have a great many flags that you can provide to turn or off certain features, compile in a different mode or introduce instrumentation to track various properties about program or library. Because each compiler has different options and specifies them in different ways, there is no universal set of flags that you can specify to all compilers and because of how many options there are, it would be ludicrous to try and outline them all here. However, it is good practice to turn on all the warnings such that you can identify problematic code and remove it when appropriate.

GCC and Clang have an almost identical set of flags with MSVC being the outlier. The flags I’d highly recommend specify whenever compiling C++ is as follows for each of the compilers.

GCC and Clang

-Wall- Turn ‘all’ warnings on-Wextra- Turn ‘extra’ warnings on-Werror- Turn warnings into errors (very harsh)-Wpedantic- Ensure strict ISO C++ Standard is Followed

g++ -std=c++17 -Wall -Wextra -Werror -Wpedantic -o hello_world main.cxx

MSVC

/W4- Warning Level 4

cl /std:c++17 /W4 /EHsc /Fe: hello_world.exe main.cxx

Compiling and Running Are Separate Steps

You may notice that it took two separate steps in order to run our program. This is because C++ is a compiled language, meaning that our source code is transformed into something else. In the case of C++, the compiler will generate binary machine code for our target platform; which in this case is our own device before running. This means the generate (machine) code is specific to the target and you cannot transferred and run on a different computer if its architecture is different. This allows the compiler to optimise your code for the target platform but does require the additional step.

This is in contrast to interpreted languages; like Python, Ruby, JavaScript etc., which will perform the conversion while the program is running but this in turn requires another program; the interpreter, to run alongside yours, taking up extra resources but it usually means your programs are more portable as they can run on anywhere the interpreter can. These are some trade-offs made when designing or using a language.

For simple programs, directly using a C++ compiler (like g++) is fine, but as your

project grows you’ll want to manage all the options and make it easy to share your code.

Next, we’ll introduce you to the CMake tool, which will help you write manage much larger

projects.

Hello, CMake

CMake is a third-party tool used to configure and build C++ projects. While there are other tools like CMake for configuring C++ compiler toolchains, CMake is the most ubiquitous within the C++ community. CMake allows use to define one or more targets that our project produces. Targets can be an executable, library, documentation or even testing. This allows a single project to build many different outputs for different platforms from a single source. Targets can also be consumed by other targets allowing more modular builds.

Adapting our hello_world Project

To start off, go back to your projects/hello_world directory and create a new file

CMakeLists.txt.

cd ~/projects/hello_world

touch CMakeLists.txt

Set-Location projects/hello_world

New-Item -Path . -Name "CMakeLists.txt" -ItemType "File"

cd ~/projects/hello_world

echo. > CMakeLists.txt

CMake Configuration Files

A CMake project is defined by a set of ‘CMakeLists.txt’ files located in the source tree

(directories containing your source code). These describe your projects targets, source

files etc.. For a simple single file project we only need a single ‘CMakeLists.txt’

alongside our main.cxx source file. Copy the contents from below.

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.22)

project(hello_world

VERSION 0.1.0

DESCRIPTION "Hello, CMake!"

LANGUAGES CXX)

add_executable(hello_world main.cxx)

target_compile_features(hello_world PRIVATE cxx_std_17)

Let’s break down our CMakeLists.txt file. First we specify the minimum required version

of CMake this project uses. This helps to ensure that any CMake features used in the

projects configuration are available to end users and collaborators.

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.22)

We then define the basic information about our project such as its name, description, version and what languages it uses.

project(hello_world

VERSION 0.1.0

DESCRIPTION "Hello, CMake!"

LANGUAGES CXX)

In order to mark our main.cxx as an executable we use the add_executable() function

where we specify the executable’s name ie. the name of the target created from the

executable as well as the source file used to make the executable.

add_executable(hello_world main.cxx)

Finally, we can add compilation features; such as setting the C++ Standard to use for

building the target, using the target_compile_features() function. Here we add the

builtin CMake feature cxx_std_17 to our executable which ensures it is built using the

2017 C++ Standard.

target_compile_features(hello_world PRIVATE cxx_std_17)

Tip

See Appendix C for more information on C++ Standards.

Building and Running a CMake Project

When building a CMake project we have to perform two steps. The first step is to configure the project. What this does is generate the build recipe(s) for your project according to your ‘CMakeLists.txt’ files. A recipes are the instructions used to actually compile your project with a single recipe being used to build one or more targets. CMake then builds one or more of these targets according to a recipe.

For our project we only have a single target which also happens to correspond to our single preset so we can simply run the following to build our recipe.

$ cmake -S . -B build

-- The CXX compiler identification is GNU 11.4.0

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info - done

-- Check for working CXX compiler: /usr/bin/c++ - skipped

-- Detecting CXX compile features

-- Detecting CXX compile features - done

-- Configuring done

-- Generating done

-- Build files have been written to: /home/user/projects/hello_world/build

We can then build the target using the following command:

$ cmake --build build

[ 50%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/hello_world.dir/main.cxx.o

[100%] Linking CXX executable hello_world

[100%] Built target hello_world

This will produce a binary called hello_world in the build/ directory on Linux and

macOS and the build/Debug/ directory on Windows. We can run our program like normal.

$ ./build/hello_world # ... or .\build\Debug\hello_world.exe on Windows

Hello, World!

Tip

The reason for Windows based builds having an additional intermediate directory

Debug/for the output is because the underlying builder(s) used on Windows can be configured to output both debug and release builds from the same recipe which is controlled with CMake’s--config=<config>flag during the build step. You can test creating a ‘Release’ build by running the following command which should now produce and executable in thebuild\Release\directory.cmake --build build --config=Release

Adding Compiler Flags to CMake Build

Remember in the previous chapter how I stated that it is good to specify warning flags in your C++ builds to catch common bugs. We seem to have abandoned them when introducing CMake, do not fret, we will reinstate them now.

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.22)

project(hello_world

VERSION 0.1.0

DESCRIPTION "Hello, CMake!"

LANGUAGES CXX)

add_executable(hello_world main.cxx)

target_compile_features(hello_world PRIVATE cxx_std_17)

if (MSVC)

# warning level 4

add_compile_options(/W4)

else()

# additional warnings

add_compile_options(-Wall -Wextra -Werror -Wpedantic)

endif()

Yes, CMake has conditionals and yes they look a little weird but this is greatly the extent I will be discussing CMake until chapter 06 when we look multi-file project structures.

“Hello, Godbolt!”

The ability to quickly test and prototype software is extremely useful however, doing so in C++ is not so easy. There’s a lot of steps that need to be taken to setup a project correctly which is good for building robust software but can slow the speed of prototyping down to a halt. Luckily there exists a platform called Compiler Explorer also known as Godbolt; which allows you to build sharable C++ programs in the browser. Here is an example “Hello, world!” on Godbolt which shows the generated assembly as well as the output from the executed binary. You can also see the godbolt instance embedded below.

Project: Guessing Game

Let us jump straight into C++ by developing a project together! This will help expose you to some common concepts from C++ and how they are used in an actual program. You’ll learn how create variables, control the flow of your program, take in user input, create functions and more! These concepts will be explored in more detail in future chapters while this one will focus on the fundamentals.

We’ll be implementing a simple number guessing game. The program will generate a random integer between 1 and 100 (inclusive). It will then prompt the user to type in a guess. After the guess is entered the program will indicate whether the guess was too high or to low or a congratulatory message if the user got it right and exit the program.

Setting Up a New Project

To begin, create a new directory in your projects/ directory called guessing_game and

create your main.cxx and CMakeLists.txt files.

mkdir guessing_game

cd ~/projects/guessing_game

touch main.cxx

touch CMakeLists.txt

New-Item -Path projects -Name "guessing_game" -ItemType "Directory"

Set-Location projects/guessing_game

New-Item -Path . -Name "main.cxx" -ItemType "File"

New-Item -Path . -Name "CMakeLists.txt" -ItemType "File"

mkdir guessing_game

cd ~/projects/guessing_game

echo. > main.cxx

echo. > CMakeLists.txt

Our main.cxx file can just be an empty main() function for now and our

CMakeLists.txt is basically the same as in “Hello, World!” with only some input values

changed to reflect this mini-project.

auto main() -> int {

return 0;

}

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.22)

project(guessing_game

VERSION 0.1.0

DESCRIPTION "Number Guessing Game"

LANGUAGES CXX)

add_executable(guessing_game main.cxx)

target_compile_features(guessing_game PRIVATE cxx_std_17)

if (MSVC)

# warning level 4

add_compile_options(/W4)

else()

# additional warnings

add_compile_options(-Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic)

endif()

Processing a Guess

First we will need to we need to ask the user for input, process that input and ensure it is in a form we expected. To start we’ll simply take in the users guess and return it to them.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

auto main() -> int {

std::cout << "Guessing Game!\n";

std::cout << "Please input your guess (1..100): ";

auto guess = std::string{};

std::getline(std::cin, guess);

std::cout << "You guessed: " << guess << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Let’s briefly go over the new concepts introduced above. First we have included a new

header <string>1 which contains the definitions the type std::string2 and

supported functions.

#include <string>

We then prompt the user with the name of the game as well as request input from the user

using the output stream std::cout, which we covered in Chapter 1.

std::cout << "Guessing Game!\n";

std::cout << "Please input your guess (1..100): ";

Storing Data with Variables

Next, we construct a new variable to store the users input in.

auto guess = std::string{};

Now this is where things begin to get interesting. This line is an assignment expression which is used to bind a value to a variable. Here is another!

auto boxes = 7;

Important

Notice the lack of a type after the

=like when we initialized astd::string. This is because we have initializeboxeswith aintliteral and thus the type is inferred. If you wanted to you could explicitly specify the type as such:auto boxes = int{7};

In C++ variables are mutable by default which means we are allowed to change it’s value.

This concept will be discussed more in

Chapter 3 | Variables and Mutability. To make a

variable constant ie. its value cannot change once it is set, we use the const keyword

after/before auto (I choose after).

const auto boxes = 7; // constant

auto crates = 4; // mutable

Tip

The

//syntax indicates a comment that continues until the end of the line. Everything in a comment is ignored by C++. You will learn more about them in Chapter 3 | Comments.

In this case of our variable guess in our guessing game program, we have (default)

constructed a temporary value with the type std::string which we then bind to the

variable named guess using the = operator. We have also used auto to allow the

compiler to deduce the type that the variable guess should have. We could have written

explicitly the type on the left-hand-side instead of auto like the example below but

this would be more verbose as we have to express the type twice. It also means that if

we change the type on the RHS we must also change it on the LHS but with auto the

compiler will do that for us!

std::string input = std::string{};

Tip

When constructing our

std::stringwe have used what is known as brace initialization. This is a modern (C++11) method for initializing objects and is used to avoid the narrowing of types. The empty{}indicates we a constructing the object in its default state, which forstd::stringis an empty string.

Receiving User Input

There are a few different ways for handling user input from the terminal in C++. For this

program we have used the std::getline()3.

std::getline(std::cin, input);

This function extracts all characters from the first argument which is of type

std::basic_istream<>4. In this case, the input stream is std::cin5. Once no

characters remain in the stream or the designated deliminator is encountered; which

defaults to '\n' (third argument), the extracted characters are then written to the

second argument which is a reference to a string of the same underlying character type.

References allow functions to read and/or modify data passed to them and have the effects

reflected on the callers side. We’ll cover references and ownership in C++ during

Chapter 4. In effect this function reads an entire line

and copies the characters into a string.

Printing with Output Streams

As we first saw in “Hello, world!” we can output text using

std::cout6 global object using the operator <<7. You may be wondering why the

“unique” syntax for out has been chosen for printing? This is because the

Input/Output8 library is more generic than just a printing facility. As the name

suggests it is a library for manipulating and using Input/Output (IO) streams. Streams

can be thought of as a pipeline between two endpoints eg. a program and the terminal

screen where data can be pushed from one end (the program) and extracted at the other end

(the terminal screen). The C++ IO library uses streams to model how data is transferred

between various endpoints like a program, the terminal screen, files etc. with the <<

and >> operators being used to perform formatted IO ie. push formatted data to and/or

extract formatted data from a stream respectively. These facilities were then used to

wrap low level IO handles such as stdin, stdout and stderr; which are used to print

and take user input, in global stream objects eg. std::cin, std::cout and std::cerr

which meant they could be manipulated using the same API and functionality provided by

the standard C++ IO library.

Note

The C++23 Standard includes a new header

<print>9 with functions likestd::println()which use the C++20 formatting library10 which make printing much more intuitive and faster. This library was directly inspired by the{fmt}library.

If you are familiar with other languages you may be wondering why << is used to push to

a streams as this operator is normally used for the left bit shifting11 operations.

We are able to use the << operator because it has been overloaded. Essentially this

means the functionality of << has been changed and customized for particular types.

Within the C++ standard library, << has been overloaded to support taking a reference

to a std::basic_ostream<>12 object as the left argument; ie. the type of

std::cout, and various builtin C++ types and library types from the standard library as

the right argument eg. int and std::string, which allows the << syntax to be used

with many different types already in C++. Overloading will be covered in more detail in

Chapter 3 | Functions.

In this program we have seen that we can chain the calls to <<.

std::cout << "You guessed: " << input << std::endl;

This is because each call to << returns a reference to the same stream passed as the

left argument, allowing you to make subsequent calls to << one after another. This can

make it easier to build up pipelines to and from streams as we can create arbitrarily

long chains.

Finally, you may notice the std::endl at the end of the chain. This is a

stream manipulator. Stream manipulators are used to modify the stream to support

different kinds of formatting. In this case, std::endl simply appends a '\n' to the

stream and flushes the underlying buffer. So why not just use '\n'? Well, you should.

Using std::endl repeatedly just to add newlines will dramatically degrade performance

because repeatedly flushing the internal buffer forces the OS the immediately display the

characters instead of allowing for the output to buffer ie. reach a large enough size to

warrant making a system call. std::endl should only be used when you want to flush the

streams buffer and place a newline eg. at the end of a program, otherwise use an explicit

'\n'.

Generating a Secret Number

Now we want some way to generate a secret number that the player will try to guess. We

also want the number to be different each time so the game is more fun but we’ll keep it

between 1 and 100 to ensure it is not too difficult. To generate our secret number we’ll

use a random number generator. The C++ standard library contains a header <random>13

which contains a bunch of facilities for generating random numbers. Update your

main.cxx file according to the snippet below.

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

#include <string>

auto main() -> int {

std::cout << "Guessing Game!\n";

auto rd = std::random_device{};

auto gen = std::mt19937{rd()};

auto distrib = std::uniform_int_distribution<unsigned>{1u, 100u};

const auto secret_number = distrib(gen);

std::cout << "The secret number is: " << secret_number << '\n';

std::cout << "Please input your guess: ";

auto input = std::string {};

std::getline(std::cin, input);

std::cout << "You guessed: " << input << std::endl;

return 0;

}

First we include the new header <random>13 so we can access the (pseudo-) random

number generation types. Next we add the lines

auto rd = std::random_device{};

auto gen = std::mt19937{rd()};

auto distrib = std::uniform_int_distribution<unsigned>{1u, 100u};

The first line (default) constructs a new std::random_device14. This is a uniformly

distributed, non-deterministic number generator. While we could generate a random number

from simply calling rd, this is considered bad practice as std::random_device14

performance degrades with use due to its entropy pool being used up. For this reason we

simply use it to seed a proper Pseudo-Random Number Generator (PRNG) such as

std::mt1993715 which is what we do on the second line. Finally we construct a

std::uniform_int_distribution<>16 which is used to uniformly generate integers

between the two provided bounds.

This sets up our random number generator. To obtain a random number we can call the distribution object, passing in the generator and returning a new random value.

const auto secret_number = distrib(gen);

Comparing the Guess to the Secret Number

Next we want to compare our players guess to the secret number.

#include <compare>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

#include <string>

auto main() -> int {

std::cout << "Guessing Game!\n";

auto rd = std::random_device{};

auto gen = std::mt19937{rd()};

auto distrib = std::uniform_int_distribution<unsigned>{1u, 100u};

const auto secret_number = distrib(gen);

std::cout << "The secret number is: " << secret_number << '\n';

std::cout << "Please input your guess: ";

auto input = std::string{};

std::getline(std::cin, input);

auto guess = std::stoi(input);

if (guess == secret_number) {

std::cout << "You guessed correctly!\n";

break;

} else if (guess < secret_number) {

std::cout << "Too small!\n";

} else if (guess > secret_number) {

std::cout << "Too big!\n";

}

return 0;

}

Before we are able to compare the players input to our secret number we must first convert the raw input into a number so they can be compared.

auto guess = std::stoi(input);

C++ offers a few functions for converting strings into numbers which all start with the

prefix std::sto*17 meaning ‘string-to’ followed by a designator for the conversion

type. Because we want to parse our input as a plain int we can use std::stoi().

Next we compare the guess to our secret_number. We use if and else if18

branches to test the ordering of the two numbers and run a separate piece of code

depending on which condition is true.

if (guess == secret_number) {

std::cout << "You guessed correctly!\n";

break;

} else if (guess < secret_number) {

std::cout << "Too small!\n";

} else if (guess > secret_number) {

std::cout << "Too big!\n";

}

Handling Parsing Errors with Exceptions

Our game is coming along quite nicely but it has one fundamental flaw. What happens if we give our game the input “abcd34” or “38574876546456476745”? We get the following two errors and our game crashes!

# input: "abcd34"

terminate called after throwing an instance of 'std::invalid_argument'

what(): stoi

[1] 27989 IOT instruction ./build/.../guessing_game

# input: "38574876546456476745"

terminate called after throwing an instance of 'std::out_of_range'

what(): stoi

[1] 1513 IOT instruction ./build/.../guessing_game

This is not ideal as it gives no way for the system to recover from the error and let the

user try again. How do we fix this? Well notice in the error message it states that an

instance of (either) std::invalid_argument19 (or) std::out_of_range20 was

thrown. What are these objects? These are known as exceptions. They are a special object

used to indicate that an exceptional event has occurred. These are pathways in our

program that we do not expect to occur but might and exceptions allow us to recover the

system without fully crashing. This is a useful mechanism for allowing systems to remain

online and perform self recovery if an error does occur.

Before we look at how to handle thrown exceptions we’ll first discuss what each of these

exceptions mean in the context of std::stoi()17. std::invalid_argument19 is

used to indicate that a general parsing error has occurred due to a bad input ie.

prefixing the input with letters eg. “abcd34”. The exception std::out_of_range20 is

used to indicate that the input value cannot fit into the conversion type. For example if

“38574876546456476745” is passed to std::stoi()17 we have this exception thrown

because the max value that can be fit inside an int is 2147483647 which is much

smaller than 38574876546456476745.

Tip

The

std::sto*function family will ‘successfully’ parse inputs like “34abc” as they extract the number from the front and will discard the rest.

Catching Exceptions

So how do we handle an exception that has been thrown? We can use a try-catch block.

When there is a chance for something to fail we place the potentially failing code

in a try block21. After a try block we put one or more catch blocks22. These

are used to define the exception handling pathway for that particular exception.

// --snip--

#include <exception>

#include <iomanip>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

#include <string>

auto main() -> int {

// --snip--

std::cout << "Guessing Game!\n";

auto rd = std::random_device{};

auto gen = std::mt19937{rd()};

auto distrib = std::uniform_int_distribution{1, 100};

const auto secret_number = distrib(gen);

std::cout << "The secret number is: " << secret_number << '\n';

std::cout << "Please input your guess: ";

auto input = std::string{};

std::getline(std::cin, input);

auto guess = int{0};

try {

guess = std::stoi(input);

} catch (const std::invalid_argument&) {

std::cerr << "Invalid input " << std::quoted(input) << "!\n";

std::exit(0);

} catch (const std::out_of_range&) {

std::cerr << "Input " << std::quoted(input) << " is too large!" << '\n';

std::exit(0);

}

// --snip--

if (guess == secret_number) {

std::cout << "You guessed correctly!\n";

break;

} else if (guess < secret_number) {

std::cout << "Too small!\n";

} else if (guess > secret_number) {

std::cout << "Too big!\n";

}

return 0;

}

Warning

While

try-catchblock’s do model a form of control flow they are very different to regular control flow mechanisms likeifstatements. You should not be usedtry-catchblocks to control the regular/expected execution pathway of a program as they are much slower nor should you throw exceptions in order to jump out to a particular scope. Exceptions should only be used to indicate that a recoverable error has occurred andtry-catchblocks being used to handle recovering from this event eg. giving any allocated resources back to the OS, as such exceptions should be used only in exceptional (pun most definitely intended) cases and when appropriate for your domain (as they can be undesirable in many situations). The main purpose of showing exceptions now is to demonstrate how to handle them not throw your own.

Allowing Multiple Guesses with a Loop

Now that we correctly handle the exceptional cases of parsing our player’s input we can

look at making the game more interactive. Only having one guess doesn’t make our game

very fun. Lets allow the player to make multiple guesses by introducing a loop! We will

want this loop to run forever with explicit mechanisms for exiting the loop. We can use

a while loop with its condition simply being true. This will create our infinite

loop. But how and when do we exit the loop? We want the loop to be broken when the player

guesses the correct number. We can do this by introducing a break statement in the

first if branch when comparing the player’s input to the secret number. break is used

to break out of the enclosing loop block. We also need the program to run the next loop

iteration if an exception occurs, skipping the comparisons. We can do this with a

continue statement within each of the catch blocks to skip to the next iteration.

Finally, be sure to move the prompt output and player input logic into the loop so they

are called each iteration.

// --snip--

#include <exception>

#include <iomanip>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

#include <string>

auto main() -> int {

// --snip--

std::cout << "Guessing Game!\n";

auto rd = std::random_device{};

auto gen = std::mt19937{rd()};

auto distrib = std::uniform_int_distribution{1, 100};

const auto secret_number = distrib(gen);

std::cout << "The secret number is: " << secret_number << '\n';

auto input = std::string{};

auto guess = int{0};

while (true) {

// --snip--

std::cout << "Please input your guess: ";

std::getline(std::cin, input);

try {

guess = std::stoi(input);

} catch (const std::invalid_argument&) {

std::cerr << "Invalid input " << std::quoted(input) << "!\n";

continue;

} catch (const std::out_of_range&) {

std::cerr << "Input " << std::quoted(input) << " is too large!" << '\n';

continue;

}

if (guess == secret_number) {

std::cout << "You guessed correctly!\n";

break;

} else if (guess < secret_number) {

std::cout << "Too small!\n";

} else if (guess > secret_number) {

std::cout << "Too big!\n";

}

}

return 0;

}

Fantastic! With a final tweak we have finished the guessing game. Our game is still printing the secret number! We can fix this by deleting the line. The final code is available below.

#include <exception>

#include <iomanip>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

#include <string>

auto main() -> int {

std::cout << "Guessing Game!\n";

auto rd = std::random_device{};

auto gen = std::mt19937{rd()};

auto distrib = std::uniform_int_distribution{1, 100};

const auto secret_number = distrib(gen);

auto input = std::string{};

auto guess = int{0};

while (true) {

std::cout << "Please input your guess: ";

std::getline(std::cin, input);

try {

guess = std::stoi(input);

} catch (const std::invalid_argument&) {

std::cerr << "Invalid input " << std::quoted(input) << "!\n";

continue;

} catch (const std::out_of_range&) {

std::cerr << "Input " << std::quoted(input) << " is too large!" << '\n';

continue;

}

if (guess == secret_number) {

std::cout << "You guessed correctly!\n";

break;

} else if (guess < secret_number) {

std::cout << "Too small!\n";

} else if (guess > secret_number) {

std::cout << "Too big!\n";

}

}

return 0;

}

Summary

This project offered a hands on way to learn many of C++ features: auto, variables,

functions, if statements, exception handling and loops! In the upcoming chapters you

will delve deeper into these concepts as well as explore many new ones. See you there!

-

https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/string/basic_string/getline ↩

-

https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/io/basic_ostream/operator_ltlt ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bitwise_operation#Bit_shifts ↩

-

https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/numeric/random/random_device ↩ ↩2

-

https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/numeric/random/mersenne_twister_engine ↩

-

https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/numeric/random/uniform_int_distribution ↩

-

https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/string/basic_string/stol ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/error/invalid_argument ↩ ↩2

Common Programming Concepts

Throughout this chapter we will cover some of the most common concepts that appear in many different programming languages and how they work in C++. None of these concepts are unique to C++ but they may work slightly different to how you are used to.

Important

Keywords are words reserved for use by the language meaning they cannot be used as identifier names for variables or functions. See Appendix A for full list of keywords.

Variables and Mutability

We first saw variables in our mini guessing game project where we used them to store the guess of the user and create our PRNG etc.. Let’s explore what happens when we try to modify constant data and when we would want to allow mutations.

Create a new project have done before, with a main.cxx and CMakeLists.txt and add the

following contents. This will act as out scratchbook project for tinkering with examples.

I won’t always go into super detail about what changes will be made between various

topics but most examples will have a full example with some being hidden behind snips

which can be exposed using the ‘eye’ button in a codeblock.

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.22)

project(main

VERSION 0.1.0

DESCRIPTION "C++ Book Examples"

LANGUAGES CXX)

add_executable(main main.cxx)

target_compile_features(main PRIVATE cxx_std_17)

if (MSVC)

# warning level 4

add_compile_options(/W4)

else()

# additional warnings

add_compile_options(-Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic)

endif()

#include <iostream>

auto main() -> int {

return 0;

}

Declaring Variables and Constants

To start with we will explore how your declare variables and constants and what happens

when you try to change the value for each. Below outlines a program that declares a

constant with the name x and assigns it the value 42 and displays the result. Very

straight forward, basically the same as ‘Hello, world!’. We then reassign x to 43 and

print the result. The question is, would this compile? Let’s take a look.

#include <iostream>

auto main() -> int {

const auto x = 42;

std::cout << x << "\n";

x = 43;

std::cout << x << "\n";

return 0;

}

When we try to compile the above we should get an error like so:

$ cmake -S . -B build

...

$ cmake --build build

[ 50%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/main.dir/main.cxx.o

/home/user/projects/common/main.cxx: In function ‘int main()’:

/home/user/projects/common/main.cxx:7:7: error: assignment of read-only variable ‘x’

7 | x = 43;

| ~~^~~~

gmake[2]: *** [CMakeFiles/main.dir/build.make:76: CMakeFiles/main.dir/main.cxx.o] Error 1

gmake[1]: *** [CMakeFiles/Makefile2:83: CMakeFiles/main.dir/all] Error 2

gmake: *** [Makefile:91: all] Error 2

The answer is a definitive no. Why? Because x in this program is a constant meaning its

value does not change over its lifetime. If x is meant to change we drop the const

keyword, allowing x to be mutated and thus making it a variable.

#include <iostream>

auto main() -> int {

auto x = 42;

std::cout << x << std::endl;

x = 43;

std::cout << x << std::endl;

return 0;

}

$ cmake -S . -B build

...

$ cmake --build build

...

$ ./build/main

42

43

Type Deduction

It is time to address the elephant in the room, auto. You may be asking;

- “What is this peculiar keyword and why are we declaring constants and variables with it?”

- “I thought C++ was a typed language, where are the types?” etc..

All valid questions and if we are to continue using auto we should address what it is

doing. auto does not introduce dynamically typed variables into C++, the type is

still there it is just inferred by the compiler. This is a mechanism called type

deduction and it allows for the type of many expressions to be resolved by the compiler

rather than the programmer. This feature was introduced with C++11 allows for simpler

expressions to be written in the language.

Take a look at the example below, both lines declare a variable with one explicitly

stating the type of x while the other lets the compiler deduce the type of y for you

but with both variables having the type int.

int x = 5;

auto y = 6;

As discussed in the chapter 02, you can still mark the type of an expression explicit by

making it explicitly known on the right hand side of the equals sign, like we did for

std::string.

int x = 5;

auto y = int{6};

Storage Duration

The primary goal of variables (and constants) is to store data. Whether that be numbers, characters, memory address etc.. How long a variable is around for (known as its lifetime) is determined by where space for the data was made available from and can be labelled by one of three categories known as “storage durations”.

So far we have seen data with automatic storage duration, which means the lifetime of

that data is tied directly to the scope it was declared in. Currently we have only been

working in the scope of the main() function, thus when we return from main(), the

variables we have declared will become unavailable.

Soon we will look at data that has dynamic storage duration. This is data whose lifetime is managed manually by the program and thus by the programmer. You must explicitly request the space for the data and remember to return it once you no longer require it.

These two storage duration categories are often tied to the notion of the stack and the free store respectively. Data with automatic storage duration is allocated on the stack allowing for the usual mechanisms of the stack to handle the allocation and deallocation of the slots used for the data, and the free store being the region in which dynamic data is located.

One we haven’t looked at yet is static storage duration. This is data that is encoded

directly in the binary of a program and thus lives for the entire duration of the

program. To give data this storage duration we declare it with the static keyword.

Global variables declared outside of a functions are implicitly static.

Data Types

The type of a value is important in C++ as it determines the permissible actions that can be performed on the value as well as determine the size of the value in memory. C++ has a great many types but we’ll begin by looking at some of the most simple, ones you will find in every program your read or write.

Scalar Types

Scalar integrals are types encoded as whole numbers. This not only includes integers types but C++ character and Boolean types.

Integer Types

An integer is a whole number. C++ has a few different integer types which have

different bit widths. The default int is 32-bits wide on most platforms. By default

integer types are signed ie. they can represent both positive and negative numbers. If

you need unsigned numbers we can use the unsigned qualifier.

const int x = -5;

const unsigned int y = 5;

If you need integers of a different sizes you can either use size qualifiers with the

int type to dictate the minimum size the integer can be. All of these can be used in

combination with the unsigned qualifier.

| Type | Full Type | Minimum Size | Signed Value Range | Unsigned Value Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

char |

char |

at least 8 | -128 to 127 | 0 to 255 |

short |

short int |

at least 16 | -32,768 to 32,767 | 0 to 65,535 |

int |

int |

at least 16 | -32,768 to 32,767 | 0 to 65,535 |

long |

long int |

at least 32 | -2,147,483,648 to 2,147, 483,647 |

0 to 4,294, 967,296 |

long long |

long long int |

at least 64 | -9,223,372,036,854,775,808 to 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 |

0 to 18,446,744,073,709,551,615 |

You can also use fixed width integer types (FWIT). FWIT have the form std::intN_t or std::uintN_t where N is the exact number of bits wide. The standard library define FWIT (signed and unsigned) for 8, 16, 32, 64 bits widths.

The bit width of an integer dictates how many values the integer can represent. As of C++20, all integers must be represented by 2s-complement which means that for signed numbers the range of values is \(-2^{N-1}\) to \(+2^{N-1}-1\) eg. -128 to 127 for an 8-bit number and for an unsigned number the range is \(2^N-1\) eg. values 0 to 255 for an 8-bit number.

In addition to these integer types there are std::size_t and std::ptrdiff_t which

are the unsigned and signed types respectively that have the max bit width available on a

given architecture, eg. 64 bits on 64-bit architecture. std::size_t is the type used

when indexing arrays or getting the size of objects.

Literals

Literals are the symbols that represent an actual value in C++ source code. They are

mostly used to initialize a variable. For example, 1 is an integer literal of type

int while "Hello" is a string literal of type const char* (ignore the meaning of

this type for now).

Literals can have a suffix operator applied to specify the literal has a specific type

or bit width. Some can be used in combination with others such as the u literal suffix

on integer literals.

| Keyword | Description |

|---|---|

u or U | unsigned |

l or L | long |

ll or LL | long long |

Additionally you can write integer literals in a different base form by changing the prefix of the literal.

const auto decimal = 42;

const auto octal = 052;

const auto hex = 0x2a;

const auto Hex = 0X2A; // capital hex digits

const auto binary 0b101010;

Integers can also be separated using a ' to make large numbers easier to read.

const auto x = 1'234'567'890;

Character Types

You’ll notice that we have included the char type in the integer list above. This is

because character types in C++ are represented using numbers, specifically char

represents ASCII code points. Character literals are specified with single quotes like

the example below.

const char x = 'a';

const auto y = 'b';

Boolean Type

C++’s Boolean type is called bool and can either hold the value true or false.

Booleans are mostly used in conditional and loop statements eg. if and while.

bool x = false;

auto y = true;

Tip

The C language; C++’s mother language, originally did not have a native Boolean type with Boolean expressions return 1 for

trueand 0 forfalse. Later in the 1999 standard of C (C99), the_Booltype was introduced to support Booleans.

Floating Point Types

C++ has three floating point types, all of which are based on the IEEE-754 standard.

Floating point numbers are used to represent decimal numbers ie. numbers that can store

fractional components. These types are the float, double and long double; with

float represent single precision (32-bit) numbers, double being double precision

(64-bit) numbers and long double being an extended or quadruple precision (128-bit)

floating point number.

All floating point literals have the type of double with the f and l literal suffix

operators specifying a type of float and long double respectively.

const auto f = -0.06f;

const auto d = 47.5768;

const auto l = -655456.457567l;

We can also initialize floating points using exponential form:

const auto f = -6e-2f;

const auto d = 475768e4;

const auto l = -655456457567le7l;

Arithmetic Operations

Integral and floating point types are categorized as arithmetic types which mean they support the common arithmetic operations like addition, subtraction etc.

#include <iostream>

auto main() -> int {

// addition

const auto sum = 4 + 6;

// subtraction

const auto sub = 10 - 5.5;

// multiplication

const auto mul = 5 * 3.2;

// division

const auto idiv = 10 / 3;

const auto fdif = 13.5 / 2.4;

// remainder

const auto rem = 23 % 4;

// --snip--

std::cout << "sum: " << sum << "\n";

std::cout << "sub: " << sub << "\n";

std::cout << "mul: " << mul << "\n";

std::cout << "idiv: " << idiv << "\n";

std::cout << "fdiv: " << fdiv << "\n";

std::cout << "rem: " << rem << "\n";

return 0;

}

Tip

- Division between two integrals performs integer division and truncates towards 0 while if one argument is a floating point then floating point division is performed.

- Remainder is only valid between integral types.

Compound Data Types

Compound data types store multiple pieces of data or are data that can take multiple values.

Enumerations

Enumerations or enums are a construct that allows you to define a type whose value is

restricted to a set of named variants or enumerators. These named constants have an

underlying integral type. Specifying the underlying type is optional ie. omit the

: type in the enum declaration.

#include <iostream>

enum class colour : char {

red,

green,

blue

};

auto main() -> int {

const auto col = colour::red;

// --snip--

std::cout << "colour internal value is: " << col << "\n";

return 0;

}

Tuple

Tuples allow you to pack multiple pieces of data of different types into a single

structure. Tuples have a fixed size/number of elements that cannot grow or shrink once

declared. Tuples in C++ are not language types but are provided by the standard library

in the <tuple> header and is called std::tuple. We create a tuple using brace

initialization (top) or using the helper function std::make_tuple().

#include <iostream>

#include <tuple>

auto main() -> int {

const auto t = std::tuple{5u, 5.34f, -345, "abc", false};

const auto u = std::make_tuple(5u, 5.f, -345, "abc", false);

return 0;

}

Tuples can be accessed using std::get<I>(t) with I being the index of the value we

want to access and t is the tuple object.

#include <iostream>

#include <tuple>

auto main() -> int {

const auto t = std::tuple{5u, 5.34f, -345, "abc", false};

const auto u = std::make_tuple(5u, 5.f, -345, "abc", false);

const auto e = std::get<2>(t); // e := -345

// --snip--

std::cout << "2nd tuple element is: " << e << "\n";

return 0;

}

You can also destructure tuples into its constituent values like so.

#include <iostream>

#include <tuple>

auto main() -> int {

const auto t = std::tuple{5u, 5.34f, -345, "abc", false};

const auto u = std::make_tuple(5u, 5.f, -345, "abc", false);

const auto [v, w, x, y, z] = t;

// --snip--

std::cout << "v: " << v << "\n";

std::cout << "w: " << w << "\n";

std::cout << "x: " << x << "\n";

std::cout << "y: " << y << "\n";

std::cout << "z: " << z << "\n";

return 0;

}

There is a specialization of tuples called std::pair found in the <utility> header

which holds just two values. The values of a pair can be extracted using the same methods

as tuples but they also have public members std::pair::first and std::pair::second

which allows you to access the data.

#include <iostream>

#include <utility>

auto main() -> int {

const auto p = std::pair{5, 'a'};

const auto [x, y] = p;

// --snip--

std::cout << "first: " << p.first << "\n";

std::cout << "second: " << p.second << "\n";

std::cout << "x: " << x << "\n";

std::cout << "y: " << y << "\n";

return 0;

}

Array Types

C++’s array type is a fixed sized container where every elements is of of the same type

and located contiguously next to each other in memory. Much like other types it is found

in the std namespace and is called; as you might of guess std::array, which You can

import from the <array> header. An element in an array can be accessed using the

subscript operator [] or the array::at() method with indices starting at 0. The

subscript operator access does not perform bounds checking while array::at() does,

meaning the latter will throw and exception if an out of bounds index is used while the

former will results in ‘Undefined Behaviour’ which may or may not crash the program.

#include <array>

#include <iostream>

auto main() -> int {

const auto a = std::array{1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

const auto e1 = a[0]; // valid

const auto e2 = a.at(5); // exception std::out_of_range

// --snip--

return 0;

}

Functions

Functions are fundamental to programming as they allow us to write reusable pieces of

code. We have already been using a function in the examples we have shown so far, that

is the main() function which is called by our OS to start the program.

Functions are defined by introducing a type (or auto) followed by the functions name,

a(n optional) comma-seperated list of parameters surrounded in parenthesis followed by

the body of the function in (curly-)braces. We call a function through its name and

suffixing parenthesis to it.

#include <iostream>

auto foo() -> void {

std::cout << "Another one!\n";

return;

}

auto main() -> int {

std::cout << "Main function!\n";

foo();

return 0;

}

Tip

A function must be declared before it can be used as the compiler has to know the function symbol (name + parameter and return types) exists however, it does not have to defined.

#include <iostream> // declaration auto foo() -> void; auto main() -> int { std::cout << "Main function!\n"; foo(); return 0; } // definition auto foo() -> void { std::cout << "Another one!\n"; return; }

Parameters

Parameters are a way to pass information into functions. The type of each parameter must be specified, using the same syntax we saw to declare a variable (without an initializer).

#include <iostream>

auto foo(const int x, const int y) -> void {

std::cout << "x: " << x << ", y: " << y << "\n";

return;

}

auto main() -> int {

std::cout << "Main function!\n";

foo(7, 6);

return 0;

}

Return Values

Functions can also return values using the return keyword. The type of the return value

is indicated either before the functions name (C-style) or using a trailing return type,

like we’ve been using for main(). When a function doesn’t a value, it’s return type is

void.

#include <iostream>

#include <sstream>

#include <string>

auto foo(const int x, const int y) -> std::string {

auto ss = std::stringstream{};

ss << "x: " << x << ", y: " << y << "\n";

return ss.str();

}

auto main() -> int {

std::cout << "Main function!\n";

std::cout << another_one(7, 6);

return 0;

}

Overloading

In C++ you can overload functions of the same name to have different implementations as long as the type signature of the function is different. This is because the type signature is part of the functions symbol and thus functions with the same name but different parameters (and possibly return type) is an entirely different function.

#include <iomanip>

#include <iostream>

#include <sstream>

#include <string>

// --snip--

auto another_one(const int x, const int y) -> std::string {

auto ss = std::stringstream{};

ss << "x: " << x << ", y: " << y << "\n";

return ss.str();

// --snip--

}

auto another_one(const float x, const float y) -> std::string {

auto ss = std::stringstream{};

ss << std::setprecision(4)

<< "x: "

<< x

<< ", y: "

<< y

<< "\n";

return ss.str();

}

auto main() -> int {

std::cout << "Main function!\n";

std::cout << another_one(7, 6);

std::cout << another_one(7.456575654f, 6.0f);

return 0;

// --snip--

This concept also extends to C++ operators, which can also be overloaded to have custom

functionality between custom types. Operators are overloaded using the operator keyword

as the function name, suffixed with the operator we wish to overload. Operator overload

functions can only take two parameters except unary operators, which can only take one.

#include <iostream>

#include <ostream>

#include <utility>

// --snip--

auto operator<<(std::ostream& os, std::pair<int, int> p) -> std::ostream& {

const auto [x, y] = p;

os << "x: " << x << ", y: " << y << "\n";

return os;

}

auto main() -> int {

const auto p = std::pair{7, 6};

std::cout << p << "\n";

return 0;

// --snip--

}

Warning

There are a few operators that cannot be overloaded such as scope lookup (

::), and member access operators (.,->,.*and->*).

Comments

Comments are a way to document code for other people, and yourself. In C++ there are two

types of comments, single line and multi-line. We’ve seen single line comments in many of

the previous examples but to reiterate, a single line comment is started with // and

any text written after it until a newline is ignored by the compiler.

// Comment on its own line

const auto x = 5; // Comment

Multi-line comments are specified using /* */ quoting ie. the comment extends from

/* comment opener and continues until */. This allows comments to extend multiple

lines or be nested amongst code (if you really want).

/*

multi-line comment

another line

*/

const auto /* int */ x = 5;

Control Flow